News

Halloween’s Dark Past: From Barbaric Rituals to Today’s Lighthearted Fun

When most people think of Halloween today, they picture cheerful pumpkin decorations, children dressed as superheroes or witches, and bags of candy being carried home after a night of trick-or-treating. It feels playful, lighthearted, and family-friendly. The modern Halloween thrives on fun rather than fear. Yet if we look further back in history, the story of Halloween is far from sweet. In fact, its origins are steeped in rituals that were often brutal, even barbaric by today’s standards. To understand how this shift happened—from blood-soaked sacrifices and frightening superstitions to store-bought costumes and bags of chocolate—we have to peel back centuries of history, folklore, and cultural evolution.

The Roots of Halloween: Samhain and the Celtic World

Halloween’s story begins with the ancient Celtic festival of Samhain (pronounced “sow-in”), celebrated in Ireland, Scotland, and parts of Britain around October 31. The Celts divided their year into a light half and a dark half. Samhain marked the end of the harvest and the beginning of winter—a time associated with death, scarcity, and the frightening unknown.

For the Celts, Samhain was not simply a party or seasonal festivity. It was a deeply spiritual and fearful occasion. They believed that the boundary between the world of the living and the world of the dead thinned on that night. Spirits could walk freely among humans, some benign, others dangerous. Families lit huge bonfires to ward off evil and gathered to perform rituals meant to appease supernatural beings.

Yet what modern audiences may find shocking is the violent side of these rituals. Archaeological evidence suggests that animal sacrifices were common, and there are historical accounts—though debated by scholars—hinting at human sacrifices during Samhain. Victims might have been chosen to appease gods or spirits, their deaths seen as necessary for ensuring survival through the long, harsh winter. Even if these accounts were exaggerated by later Roman chroniclers eager to paint the Celts as savage, it remains undeniable that Samhain carried an atmosphere of dread, fear, and violence.

Masks and Disguises: Protection, Not Play

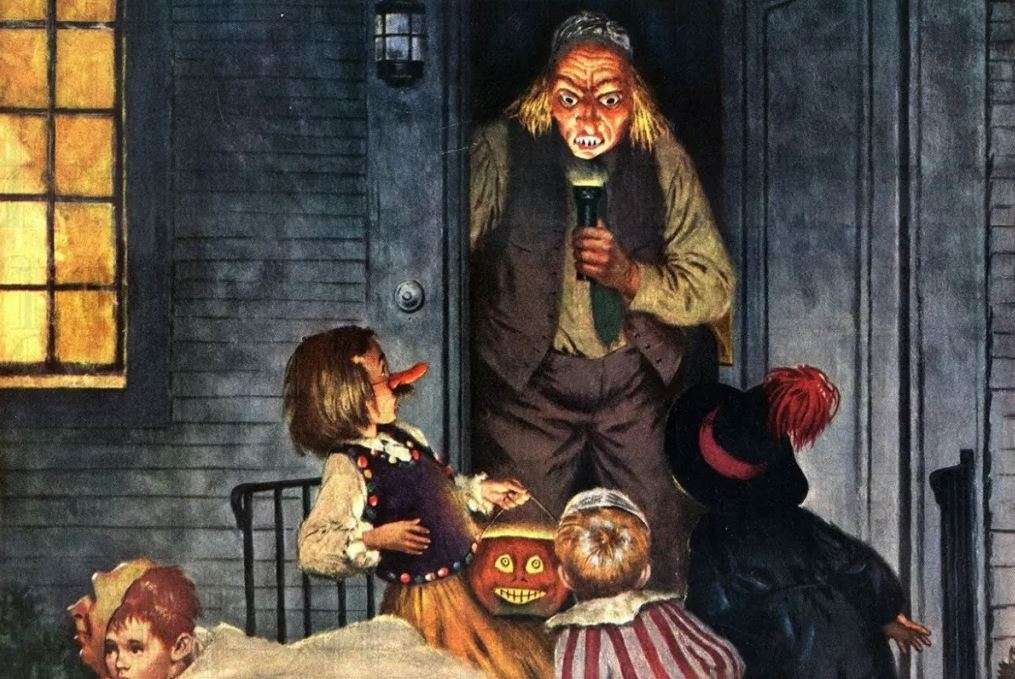

Costumes are one of the most recognizable features of Halloween today, but their origins were grim rather than entertaining. During Samhain, people wore animal skins, grotesque masks, or ash-covered disguises not to look cute or win prizes, but to confuse or scare off evil spirits. The logic was simple: if spirits walked the earth, one needed to blend in with them or frighten them away.

Instead of princess dresses or pirate outfits, imagine villagers cloaked in bloody hides of animals, faces painted with soot, carrying burning brands from the communal fire. These disguises were a survival tactic, a kind of magical camouflage in a world where people genuinely feared that malevolent forces could cause illness, crop failure, or death. Halloween attire in its earliest form was never about fun; it was about warding off threats in a world where fear was a daily reality.

The Role of Fire: Bonfires as Protection and Power

Another strikingly barbaric aspect of early Halloween lies in its fire rituals. Bonfires were central to Samhain, and they were not merely for warmth or light. These fires were sacred, often built on hilltops, and believed to have protective power. Villagers would throw the bones of slaughtered animals into the fire, creating what were called “bone-fires”—the linguistic ancestor of our word “bonfire.”

The fire was a place of sacrifice, where crops, animals, and possibly even human lives were offered to unseen powers. After the rituals, participants would take embers back to their homes to reignite their hearths, symbolizing a renewal of life blessed by sacred flames. It was a ritual blending survival and superstition, rooted in the fear that winter would bring famine, disease, and death if the gods were not appeased.

Today’s glowing jack-o’-lanterns or cheerful backyard fire pits feel worlds apart from the original bonfires that once burned with the smell of blood and bone.

The Influence of the Church: From Pagan Fear to Christian Morality

As Christianity spread through Celtic lands, the Church sought to stamp out these pagan practices. But as often happened in history, the easiest way to absorb pagan traditions was to Christianize them. Thus, Samhain was rebranded as All Saints’ Day on November 1 and All Souls’ Day on November 2. October 31 became known as All Hallows’ Eve—later shortened to Halloween.

This transition did not erase the darker aspects of the holiday immediately. Instead, old pagan customs blended with Christian theology. People still feared spirits of the dead, but now these spirits were reinterpreted through a Christian lens—as souls trapped in purgatory or demons sent to tempt the living.

One practice that arose during this period was “souling.” The poor, often children, would go door to door begging for “soul cakes” in exchange for praying for the souls of the dead. On the surface, this might sound like an innocent precursor to modern trick-or-treating. Yet imagine the scene: ragged, hungry children knocking on doors, pleading for food in the name of the dead. The undertone was one of desperation, hunger, and fear rather than joy. Refusing to give could be interpreted as denying prayers for one’s ancestors, casting a spiritual shadow over an entire household.

Witch Hunts, Devils, and Demonic Imagery

As Europe moved into the late medieval and early modern eras, Halloween became increasingly associated with witchcraft and demonic forces. The night of October 31 was considered particularly dangerous, a time when witches gathered, demons roamed, and the devil himself might appear.

The imagery of witches flying through the night, of black cats, bats, and cauldrons—all of these were rooted in genuine terror. Communities persecuted women suspected of witchcraft, sometimes torturing and executing them in public. Halloween became tied to these fears, evolving into a night when people genuinely worried about spiritual attack or possession.

Contrast that with today’s world, where children dress up as “cute witches” with sparkly hats and plastic broomsticks. The playful iconography masks a much darker reality of the past: that women were accused, beaten, and killed under the suspicion of consorting with dark forces on this very night.

From Fear to Mischief: The Rise of “Trick”

In Ireland and Scotland, Halloween also carried traditions of mischief, but these were far from harmless pranks. Young men roamed the countryside overturning carts, breaking fences, or setting fires to haystacks. Mischief was sometimes tolerated as a release of social tension, but it could easily turn destructive and violent.

By the time Irish and Scottish immigrants brought Halloween traditions to America in the 19th century, the holiday retained a reputation for vandalism and lawlessness. Newspapers of the late 1800s frequently reported Halloween riots, broken windows, and terrified townsfolk. What is now reduced to toilet-papering trees or soaping windows once had a much more destructive edge.

The American Transformation: Candy, Costumes, and Commerce

So how did Halloween transform from a night of blood, fire, and fear into one of costumes, candy, and cartoons? The answer lies in modernization, urbanization, and commercialization.

By the early 20th century, communities in the United States grew tired of the destruction associated with Halloween. Civic groups, schools, and parents began promoting structured parties, parades, and family-friendly activities. Halloween costumes became less about frightening spirits and more about entertaining children. The “trick” side of this holiday gradually softened into playful pranks, while the “treat” side grew with the rise of mass-produced candy in the mid-20th century.

By the 1950s, trick-or-treating was established as a widespread tradition, perfectly suited to suburban neighborhoods. The violent and chaotic aspects of Halloween were carefully managed, replaced by a consumer-friendly holiday that candy companies, costume makers, and toy manufacturers eagerly embraced.

The barbaric roots of Halloween were buried under layers of commercial gloss, until the average child no longer had any idea that the day once carried genuine fear of death, demons, and sacrifice.

Why We Forget the Darkness

One reason the barbaric past of Halloween is so often forgotten is because modern culture thrives on sanitization. Holidays are repackaged to fit contemporary sensibilities. Just as Christmas absorbed pagan solstice traditions and Easter adopted fertility symbols, Halloween underwent a cultural makeover. It became less about fear and death and more about play and profit.

Yet perhaps there is also something deeper at work. By laughing at ghosts, dressing as monsters, and turning witches into cartoon characters, we domesticate fear. We take what once terrified our ancestors and make it safe, even fun. It is a way of coping with the eternal human reality of death and the unknown.

Echoes of the Past

Despite its transformation, Halloween still carries faint echoes of its barbaric origins. Horror movies exploit the fear of masked figures and restless spirits. Haunted houses simulate the fear of death and violence. Even trick-or-treating retains a symbolic trace of ancient exchanges with the dead—offering something to prevent harm.

The barbaric rituals of fire, disguise, and sacrifice have been tamed, commercialized, and made child-friendly. Yet beneath the costumes and candy lies a reminder: Halloween was once about survival in a world where death was closer, where winter meant famine, and where unseen forces were genuinely feared.

Conclusion: From Blood to Candy

Halloween today is a playful holiday that thrives on sugar and laughter. But its history reminds us that it was once a night of deep fear, violent ritual, and barbaric survival strategies. Samhain’s sacrifices, bone-fires, witch hunts, and violent pranks reveal a holiday far removed from the child-friendly event it has become.

Understanding this history adds richness to Halloween. When we carve pumpkins, light candles, or put on costumes, we are engaging—unknowingly—with traditions born in blood and fear. It is a fascinating example of how culture transforms the terrifying into the playful, the barbaric into the commercial, and the sacred into the secular.

Halloween has traveled a long road from the bone-fires of the Celts to the candy-filled streets of modern America. What was once brutal is now benign. What was once about appeasing spirits is now about entertaining children. Yet perhaps this is the true magic of Halloween: its ability to transform, to mask, and to remind us—underneath the costumes and candy—that the shadows of the past are never entirely gone.